Spaceflight lessons inform medical technology research

You also researched and developed a robotic device. What does the robot do?

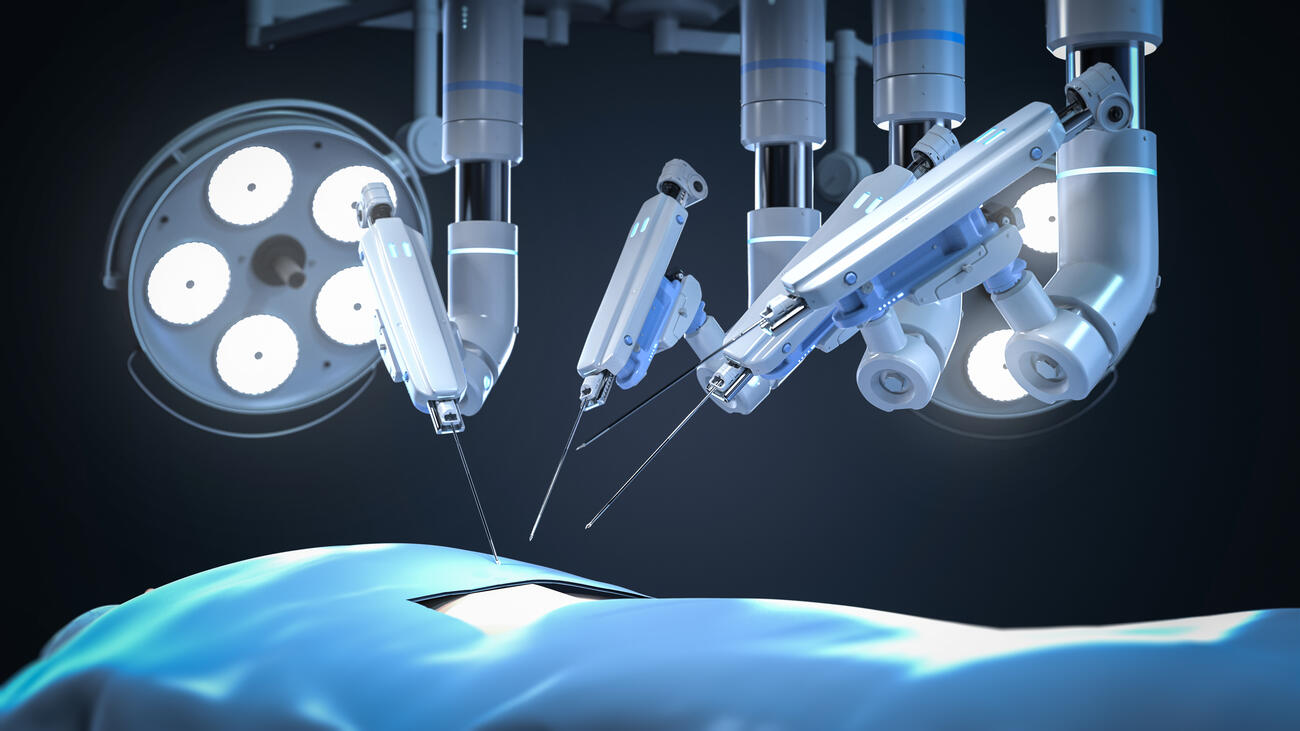

I worked on developing a robot that can find blood vessels in the arm and place an intravenous catheter autonomously. This step can be a choke point in any health care system with a lot of patients moving through it. Our research team’s goal was to reduce waiting times and improve patients’ comfort. We started with an off-the-shelf research robot and developed its capability to attach and use an ultrasound probe to identify blood vessels and make 3D maps of them. We had not yet taught it how to actually insert the IV in a human arm, but when we conducted surveys that asked experiment subjects if they would allow the robot to do that, they all said yes. This showed that they trusted the technology to advance to the next step. At UW, I am seeking partners or supporters who can help us build out the technology to the point where the robot can place a needle in the arm and secure the IV.

What barriers to automation exist in the health care environment?

The main barrier comes more from lack of trust in the system than in the system’s capabilities. But the public does trust many automated systems in safety-critical environments. For example, traffic lights are automated, use rules that aren’t immediately obvious to end users, and control the high-speed movement of several-ton vehicles millions of times per day across the US. My research asks: What does it take in terms of the reliability of the underlying technology and capability of humans interacting with that technology, to make our automations as trustworthy as traffic lights?

How does your knowledge of the human body inform your work as an engineer, and vice versa?

The human body is a system of systems that all have their own requirements and performance characteristics. Pathology occurs when systems don’t meet requirements, impacting their performance which leads to dysfunction in the rest of the body systems. On the engineering side, my work is very much informed by my experience and training as a clinician. Any engineering system that requires interaction with a human will have to compensate for the vast, but still finite, variation in human forms, behaviors and abilities.

What are some ways you helped manage the risk for human spaceflight when you worked at NASA?

NASA is primarily an engineering organization and treats humans as a critical system component. The risk is that they cannot perform their tasks. If the crew doesn’t fire the rockets at the right time, then the vehicle could crash or go into the wrong orbit. Some of the questions we would pose could include: What is the risk that the crew would not be strong enough to do spacesuit activities if the food and water system isn’t producing enough calories? Or, what is the risk that bones will fracture during a Mars landing, due to the deconditioning that occurs during a long time floating in microgravity? I am most interested in asking what technology can be used to address these risks. Can we make medications that take the place of exercise? Can we automate some aspects of care so the crew’s medical officer isn’t a single point of failure for the medical system?

Describe your collaboration with UW’s College of Engineering.

In the short term I’m planning to apply for external and internal funding with College of Engineering co-investigators, to develop a course on either space medicine or medical devices that allows both medical students and engineering students to work with each other on clinical problems. I am also interested in training clinicians, engineering PhD students, and postdoctoral fellows in joint projects. I want to contribute to making Wisconsin a hub for technological development related to commercial spaceflight. I also want to study ways to improve access throughout the state, including in rural areas, to the incredible health care available here.

Why is UW–Madison a great place to be doing your work?

One of the deciding factors in coming to UW–Madison was a discussion I had with Dr. Jim Berbee, who teaches in the emergency department and is a key supporter of the school. He explained that there is a robust resource base of partners on the UW campus and in the surrounding community and local industry who are eager to help us build the tools we need to answer our research questions related to automation in the clinical workspace. I am looking forward to building a network of entrepreneurial contacts and alumni supporters who can help us move our research questions forward.

link